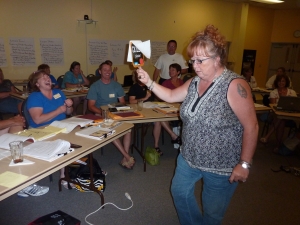

Maureen Malloy, Chesapeake Region Project Archaeology Coordinator, shares her views on public archaeology in the 21st Century.

As I sit down to finish this Project Archaeology blog entry the calendar says December, but the thermometer says spring –it’s 65 degrees this afternoon! Washington DC has long, mild, beautiful autumns–when I worked as a field archaeologist it was always my favorite season.

I got my first opportunity to do public archaeology in 1983 when I was hired to supervise field and lab volunteers at a Late Woodland site in Virginia. I didn’t have any training in public outreach, and–other than being a teaching assistant in grad school– I had never taught anyone or anything. But I immediately fell in love with the public part of my work and before I knew it I was showing high school students how to do surface surveys, bringing artifacts to elementary and middle schools all over the county, organizing family dig days, working with Scouts, and teaching adult education classes on local archaeology at the community college near the site.

Twenty-eight years later, as the Manager of Education and Outreach at the Society for American archaeology, and the Chesapeake regional coordinator for Project Archaeology, I am still doing public archaeology. Although I no longer work in the field, yesterday I spent the day at a DC public elementary school. Last week I talked to a group of Girl Scouts about careers in archaeology. During the spring and summer I participated in local archaeology festivals and an archaeology summer camp, and did teacher workshops. On the surface, the public archaeology I’m doing today might not look so different than what I was doing back then– but in reality it is quite different.

Thirty years ago public archaeology—for me, and many of my colleagues –was pretty much limited to what I described above: classroom visits, site tours, working with volunteers in the field and lab, creating brochures or interpretive panels, organizing the first Archaeology Month celebrations in our states. Important activities, to be sure—emphasis on the word activities. And our primary reason for climbing out of our caves, excavation units, and labs, into the glare of the public spotlight? As a profession we were driven primarily by our concern over the looting and destruction of archaeological sites. Our professional societies including SAA issued ethical mandates for doing and supporting public outreach and education, which was seen as, if not the answer, then an important part of the solution to archaeology’s most intractable problem.

Public archaeology has always had myriad definitions or meanings and they continue to evolve and grow with the field. Thirty years ago it generally meant “government” or “CRM” archaeology. Much public archaeology then was driven by the explosion of CRM projects that followed the historic preservation legislation of the late 1970s, and a growing awareness that if public money was funding archaeology then there better be clear public benefits. So we invited the public to help us on our sites and in our labs. We presented our archaeological finds and research to local school kids, set up displays at the local library, or showed slides at the local Rotary Club meeting after the coffee was served. We were eager and enthusiastic to share our expert knowledge and expected the public to accept and respect it. We would convert everyone we spoke to – they would all become stewards of our endangered archaeological and historic resources. The end result would be a public that came to understand and value archaeology and the need for preservation and protection of sites. And to some extent I think this strategy was successful. The Harris poll commissioned by SAA, NPS and other archaeological organizations in 2000 found that most Americans support. But looting and destruction of sites continues at an alarming rate, and fueled by E-Bay and a host of complex social issues, the illegal sale of artifacts has skyrocketed. Archaeological programs are being gutted in many states and I think we can all agree that we are not going to see an expansion of support for archaeology and historic preservation at the federal level in the current economic and political climate. We will be lucky if we can hang onto the existing protections for cultural resources. Now more than ever we need the support of the public–our many publics.

Changes in the field of public archaeology over the past two decades have created opportunities for working with the public in deeper and more meaningful ways. These new approaches can help us create the kinds of alliances we need to preserve archaeological and historic sites. Perhaps the most important change in the discipline is that communities now play a much bigger role in archaeology. Rather than simply the recipients of what professional archaeologists have learned, or the labor in our labs and excavation units, communities are actively engaging in all aspects of some archaeological projects. Projects may now be initiated and led by communities themselves, who invite us in to help. Public archaeology is now less of a one-way street designed by and for archaeologists to meet the needs of our discipline , and more of a shared endeavor to meet common goals. Although I find this an exciting and welcome change, I can’t say that all of my colleagues share this this view!

For me these changes in perspective and practice began when I read What this Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village by Janet Spector. By 1994 when I read this book, I was the head of the education department at an archaeological park. I was reading the scholarship on interpretation, education and museum practice. I attended the museum meetings and no longer the archaeology meetings and my subscription to American Antiquity had lapsed. Had I read Ian Hodder’s seminal 1991 AA article Interpretive Archaeology and Its Role sooner, I might have had my conversion experience a few years earlier! But Spector’s book changed everything for me. My work was in prehistoric archaeology in the eastern US and until then I had never even considered working with a descendant community. I immediately changed the way I developed public programs at the museum, involving the communities near the museum, and overhauled the teacher –training I did. I no longer felt comfortable teaching about native peoples from just an archaeological perspective. My work became more about partnership and collaboration.

Since then I have become even more interested in how archaeology can inform and help solve contemporary problems. Although I continue to be alarmed over the looting and destruction of archaeological sites and I include a stewardship message in all of the public work I do, combatting this problem is no longer my raison d’etre for doing public archaeology. So while I was in an elementary school classroom this week, it was as part of year-long program I am doing at the school, not a one-time show and tell visit with artifacts. I ‘m using Project Archaeology’s Investigating Shelter curriculum guide to help teach science and social studies, which has been cut from the 5th grade curriculum this year. The teacher I am working with wants me there, not for some special enrichment experience, but because she sees that archaeology can help teach the standards and help her kids pass the 5th grade assessment they will take this spring. The educators and administrators I meet with see the quality and potential of these PA materials and are especially intrigued by the cultural relevance aspect of the curriculum, since we live in such a multicultural environment. The stewardship piece of Investigating Shelter is important to me as an archaeologist, but frankly less important to the teachers I work with. But it is a win-win situation for the discipline and the schools.

The changes I have experienced personally have been matched by developments in the discipline. Though communicating about archaeological research to the public remains an important part of public archaeological practice and an important ethical responsibility, education and outreach are now generally recognized as just one aspect—one set of practices—of the much broader field. When the journal Public Archaeology was launched in 2000 it described itself as:

…the only international, peer- reviewed journal to provide an arena for the growing debate surrounding archaeological and heritage issues as they relate to the wider world of politics, ethics, government, social questions, education, management, economics and philosophy. As a result the journal includes groundbreaking research and insightful analysis on topics ranging from ethnicity, indigenous archaeology and cultural tourism to archaeological policies, public involvement and the antiquities trade… Key issues covered in the journal include: The sale of unprovenanced and frequently looted antiquities; The relationship between emerging modern nationalism and the profession of archaeology; privatization of the profession; human rights and, in particular, the rights of indigenous populations with respect to their sites and material relics; representation of archaeology in the media; the law on portable finds or treasure troves; archaeologist as an instrument of state power, or catalyst to local resistance to the state. http://www.maney.co.uk/index.php/journals/pua/

I believe that we will gain true public support for archaeology and historic preservation only when we can demonstrate how archaeology can be of use in the real world to our real publics. When I leave work tonight I am headed to a meeting of my local watershed protection group. For a number of years now I’ve been concerned about how the belongings of the homeless are gathered as trash when we do our park clean-ups twice a year. The organization sees the environmental problems caused by people living next to the creek. As an anthropologist I see people who, because they do not have permanent homes, are not considered a part of our community. That has been bothering me for quite a while. So last week I had coffee with a grad student named Courtney Singleton at the University of Maryland who has done pioneering work with Larry Zimmerman in Indiana on the archaeology of the homeless. Courtney and I are now planning to do an archaeological survey of the homeless living in the park . I hope the data we gather will help change the policy of the environmental group, but I plan to share it with the County officials as well. I hope it will contribute to a better understanding better understanding of the homeless members of our community and lead to improved services.

In 1983 I might have been interested in doing an archaeological survey of the park to see what it can tell us about local pre/history, and then telling that story with slides in the community center. I would actually still like to do that, but what’s more important to me now is seeing how archaeology can be used as a tool to make a positive change in the community where I live.